TOC

Anselm Kiefer was born in Germany at the end of the Second World War. Growing up among the ruins he developed his entire poetics from them, combining painting and sculpture in a decidedly unique way. Venice, at the same time, is the city of ruins par excellence: all it has to offer is its great past. It is therefore singular that for the 1600 years of the city Palazzo Ducale chose the German artist to talk about Venice. Not that there is anything wrong with this choice, on the contrary, but already from these premises, we could imagine a work in a minor tone.

To better understand how Kiefer subverts expectations, creating a monumental work, we need to take a step back and understand what Venice is today. Having entered its 17th century, the city is like those clinically dead patients hooked on a respirator. The population is a fifth of what it was 70 years ago, tourism is the only economic activity and the whole city looks much more like Disneyland than an open-air museum. We are perhaps facing the most beautiful place in the world, but all this beauty only underlines the decadence into which the city pours. An unstoppable and fatal decline.

Another artist could have reflected on this, giving birth to a melancholy and elegiac work on the past glories that will not return. Kiefer’s genius, on the other hand, manifests itself in subverting this perception: Venice is so big precisely because its ruins scream at us about its past. But let’s take a step back.

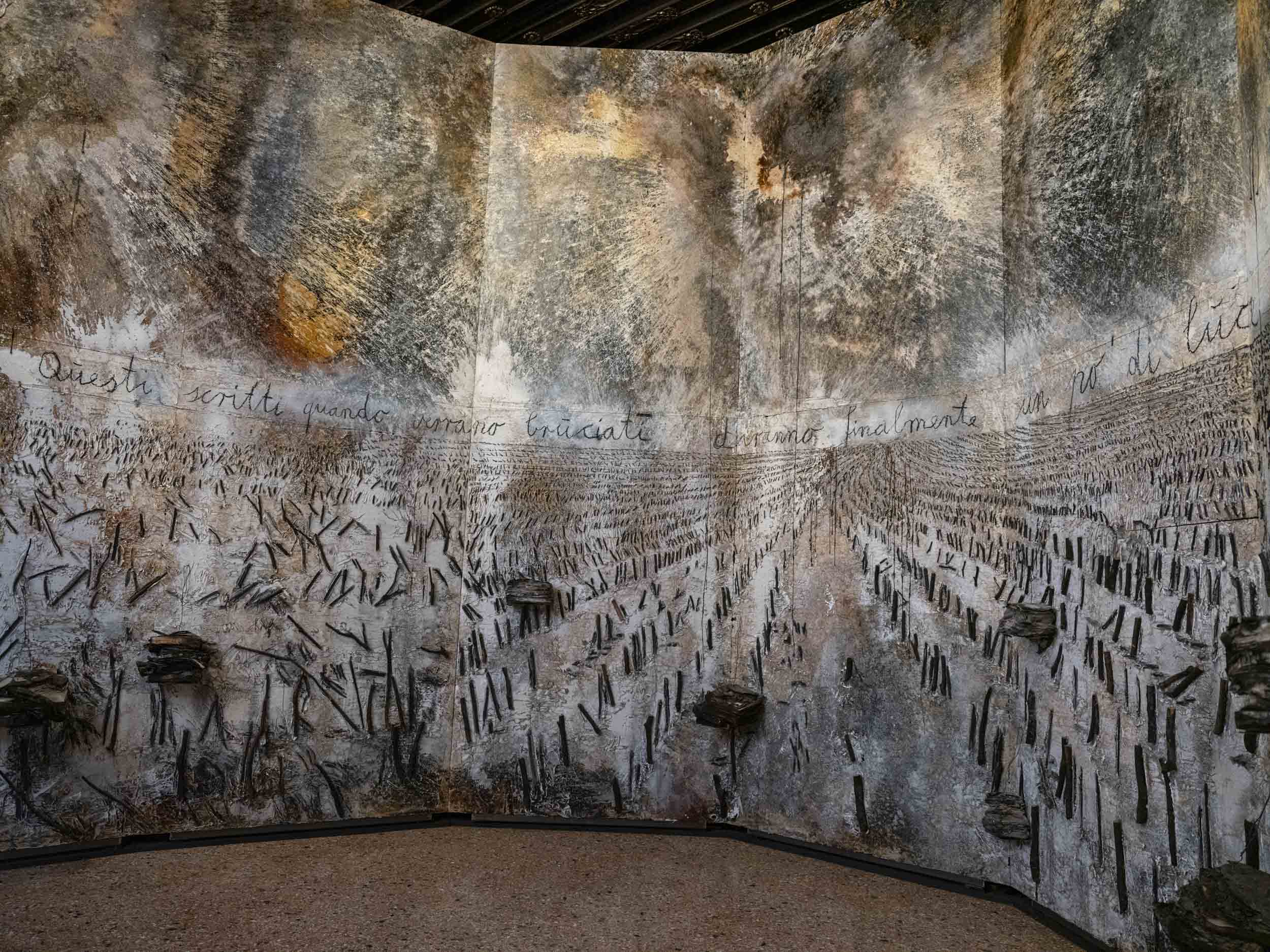

<a href=“https://palazzoducale.visitmuve.it/it/mostre/mostre-in-corso/anselm-kiefer/2022/02/22299/anselm-kiefer/"http://google.com")" target="_blank” rel=“noopener noreferrer”>"Questi scritti, quando verranno bruciati, daranno finalmente un po' di luce" (These writings, when burned, will finally give some light) is a phrase by Andrea Emo, an unrecognized 20th-century Italian philosopher. I admit that I have not read it, so I am not the right person to explain the work, but I’ll try to summarize it as follows. Speaking of God, he affirms that God can only deny himself: he will never be able to say “I am this”, but simply deny himself, for example by creating reality. Only then will we be able to find him in his absence. In very poor words (further massacring the work of this philosopher) we could say that things are noticeable only when they disappear.

This poetics is exactly Kiefer’s poetics, which is based on recollection and decomposition. When the artist first read Emo’s thoughts in 2015, he noticed how it was in line with his works. Coincidentally, Emo descends from a noble Venetian family, as if to act as a bridge between this concept and Venice.

Let’s come to Venice. In the previous room, Tintoretto paints the immense canvas of “The Paradise” where in the sky the Madonna intercedes for the city before God. Next to the most important room of the ducal palace, Kiefer stages the history of Venice, as he sees it. Ruins give way to the splendor and the battles won: a view of the lagoon, the vineyards, the empty coffin of San Marco, and the Doge’s palace itself in flames. Venice painted by the artist is not only already dead, but it has always been dead! It is this sense of loss and decay that for Kiefer marks the history of the city as if its builders had erected a posthumous monument dedicated to themselves.

Certainly, it was not like that, Venice has been a living and vital city for a very long part of its history. However, observing its uniqueness and its grandeur, one wonders if, more or less consciously, whoever built it did not think about the after. However, Kiefer is not the first, more or less consciously to try all of this. Ruskin in “The Stones of Venice”, worried that the city could be destroyed shortly thereafter, makes a detailed catalog of his architecture as if to preserve its memory.

The interpretation could be Tintoretto, whose colors Kiefer borrows. In painting the glory of Venice he uses a sometimes a dark, almost dramatic trait. In his paintings, there is not the light-heartedness of Veronese, or the civic commitment of a Vasari, nor the typical French pomp, but a melancholy that is precisely that of a late summer day in Venice. So, as I left, I think I understood the provocation: even the paintings of the Venetian Renaissance masters are ruins left for those who would come later. Kiefer is credited with having wanted to continue to embellish this stone sarcophagus of the Venetian culture which is the ducal palace.

It is the exhibition of the year for two simple reasons: it is aesthetically satisfying and includes the city of Venice. There is no need to add anything else. Bravo.